|

There is real joy in re-visiting a book that I read decade(s) earlier: it’s an experience of the familiar and treasured and the experience of the new, simultaneously. Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451 has been sitting on my shelf for a couple of years now, and yesterday I decided to read it and see what it could tell me as a 32-year old.

It turns out that it could tell me quite a lot. From the first stunning line of the book—“It was a pleasure to burn”—to the last, Fahrenheit 451 is a powerful, stomach-churning read. Guy Montag is a fireman and his job, like that of his colleagues, is to burn books. But the “pleasure” that Montag takes in burning the pages is complicated and threatened by meeting Clarisse, a teenager who asks him questions which make him start to pay more attention to the life he is living. What made firemen start setting fires when before they apparently stopped them? How did he end up married to his wife? What can he do to change this society? How can he change from the person he is to a person who understands books and is changed by them? Montag’s general dilemma is, I think, frustratingly familiar to a lot of people. Sometimes we see that we aren’t living the lives that we should—that perhaps in some ways we aren’t living at all—but it can be terribly difficult to understand how we can change when the familiar is safer. Fahrenheit 451 is a fascinating exploration of what happens to a society when people decide that they no longer want to read books: that they would rather consume and in turn, be consumed. Originally published in 1953, the book is exceedingly relevant today, when we get a lot of “information” from sound bytes, headlines, and even fake news stories. We’re dealing with questions today like where do we get the “truth,” how we do reach people who believe the exact opposite that we do and who are equally convicted, and how do we protect “essential” liberties and respond when they are threatened? I would have liked to have seen a more nuanced representation of women and other minorities in Fahrenheit 451, although I suppose that goes against part of Bradbury’s message here and in his Afterword (where he says “For it is a mad world and it will get madder if we allow the minorities, be they dwarf or giant, orangutan or dolphin,…to interfere with aesthetics.) Still, I’m left wondering what role other people—besides white men—would play in the community which Montag escapes to. I guess that, as Bradbury says in his Afterword, he left that for other writers to explore. Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451 is a slim, dense read that reminded me anew of the purposes that books serve. Of the power they (and their stories) have to anchor us, to fulfill us, and to challenge us. And I think it’s an important reminder to keep our eyes open; to remember the danger in closing our eyes to the things that frustrate, disturb, or anger us, and to refuse to disconnect from our communities and our society. What we value, matters. What we love, matters. What we tolerate and don’t tolerate, matters.

2 Comments

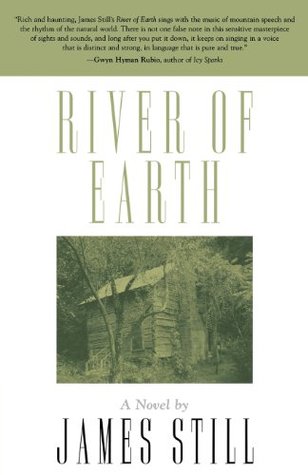

When I was growing up, Southern Appalachia was a mystery, a region of the United States that was (and to a large degree, is) often denounced, caricatured, and stereotyped. When I began deciding what area of American literature I wanted to focus on in my graduate program, I chose Southern Appalachia. I wanted to learn more about the region and challenge the stereotypical representations of it—the hillbilly and Deliverance, among them—by studying the voices of people who live(d) in Southern Appalachia and who love(d) it. James Still’s River of Earth is a beautiful novel which scholars frequently put into conversation with Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath. A much slimmer, faster read, River of Earth is just as impactful as Steinbeck’s giant. Told from the perspective of a young, unnamed boy, we learn that the Baldridge and Middleton families are struggling to survive economic hardship, that the boy’s parents fight about whether they should be a farming or mining family, and that the boy must decide which communal and familial values he wants to embrace as he matures and which he wants to reject. River of Earth is a compelling, tender coming-of-age story set in Eastern Kentucky that offers insights into a region that is often uniformly portrayed and/or misunderstood. Though it was published in 1940, the same year as The Grapes of Wrath, it remains relevant and timely. [Think for a moment about the uproar when Hillary Clinton said in 2016: “we’re going to put a lot of coal miners and coal companies out of business, right?”] I think that part of our Post-Trump election project is to consider how little we actually know about people with other backgrounds and/or beliefs than us and try to educate ourselves about American (and international) diversity. We do this partly through reading. We shouldn’t expect River of Earth to tell us everything we need to know or everything that’s important about Southern Appalachia (because a big part of the problem is thinking that any one person can speak for an entire region or group of people), but it’s a good start. |

About me.Give me that HEA, please.

Join my mailing list.Want to receive a weekly email with links to my latest blog posts? Sign up below!

Archives

April 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed