|

I think I’m good about reading the books. Less good about reviewing the books. So here’s a quick thoughts round-up about some of the books I’ve been enjoying lately!

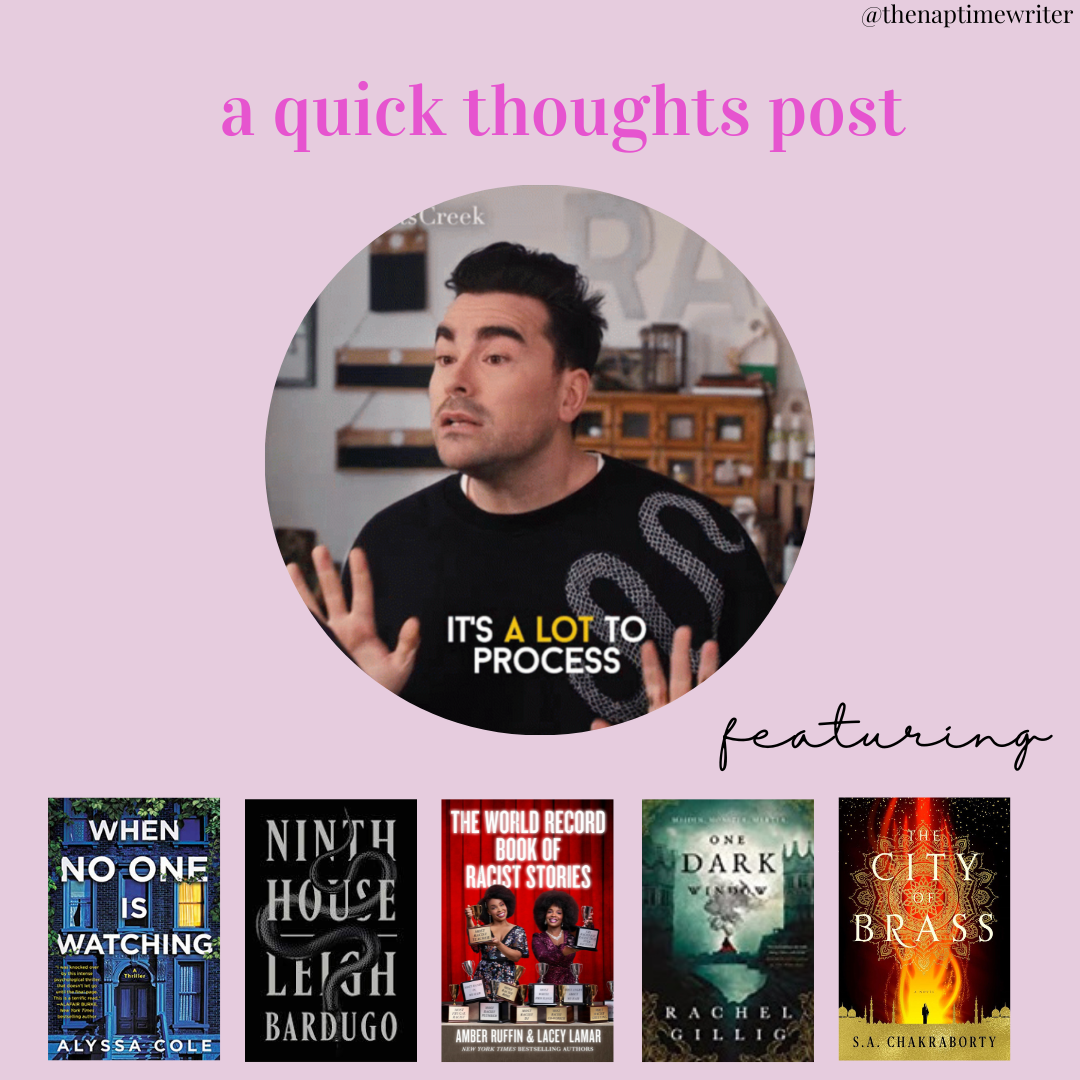

Have you read any of these? If not, have you read any other books for fun that you really enjoyed but didn’t review? When No One is Watching by Alyssa Cole. A thriller about how insidiously evil gentrification can be, orchestrated by white people—wearing things like Lululemon pants, for example—who care nothing about Black communities and think Black lives & livelihood are disposable. This book is unsettling and tense, with an explosive ending. 4.5 stars, out now. Ninth House by Leigh Bardugo. A dark academia book that had me going “huh?,” “oh,” & “oh shit, that’s horrible,” this is a weighty, smart, & compelling read that I’m honestly still parsing. Technically I think this is a 5 ️star read—it’s so well written—but for some reason I never emotionally connect to the author’s books. Out now. The World Record Books of Racist Stories by Amber Ruffin & Lacey Lamar. (thanks to @grandcentralpub for the free copy; all opinions my own.) This book is a series of anecdotes drawn from the authors’ lives & their loved ones’ detailing the racism they’ve experienced (of so many different types, in so many instances) & white privilege. The book is funny, incisive, & sharp & it gave me quite a lot to think about. 4 ️stars, out now. One Dark Window by Rachel Gillig. Another dark fantasy that will really grip you with tension. It’s a story of a girl with a secret monster inside her. There are lots of secrets & some steam! 4.5 ️stars, out now, part of a series. The City of Brass by S. A. Chakraborty. Starting this on audio really helped me get into this fantasy. It’s an immersive story with lots of threads & lots of possibility for danger. I have very little idea about where the series is going next bc it is so unpredictable & I love that. 4.5 stars ️, out now.

0 Comments

Thanks to the publisher for the complimentary finished copy. With that being said I chose to read this book via audio. All opinions provided are my own.I’m going to start this review with the caveat that I did not know a lot about outer space before beginning Moiya McTier’s The Milky Way: An Autobiography of Our Galaxy. (I still wouldn’t call myself an expert but that’s no fault of McTier’s 😆). But this book enhanced my understanding of how big space is so much (trying with all of my willpower not to say astronomically 🤣). Wow, I really had no idea. There were so many other “wow” kind of moments as I listened. Moments when my mind boggled. Moiya was easy to listen to. McTier—an astrophysicist & folklorist—is clearly very passionate about their book & the subject & the creative project the author took on by dramatizing the Milky Way’s life is admirable. But sometimes the dramatization goes too far for me, like when the Galaxy discusses suicide ideation because of how the Galaxy created the black hole “Sarge.” My knowledge of space is so limited that honestly I’m not sure what level this book is best for 😆. I learned a lot, but quite a bit went over my head as well—mostly because I didn’t always have the time or opportunity or ability to absorb it all. But again, that’s not a fault of the book—I’m sure those facts will please a lot of people. Overall I’m glad I checked this one out. It did what I hoped it would do: teach me more about space & even changed my understanding of it. 3.5 ⭐️. Out now.[ID: a white woman holds a copy of the book in front of a plant stand.]

To enter my Giveaway, check out my Instagram post here.Save Yourself is the best kind of memoir, especially for scary days like these: it’s funny & hard-hitting, tackling topics like Little Gay Kid-Oweens & Catholicism with equal verve. It’s smart & irreverent; it’s exceptional storytelling with a lot of heart.

. . Cameron Esposito describes herself as a “queer gay lesbian human being” who grew up in a family & community where Catholicism reigned. She came out at age 20 & in her memoir traces how she found her way to becoming a comic and an advocate for other comics. . . Cameron’s had a really interesting life & maybe more important, she tells a good story. . . But as funny as it is, Save Yourself isn’t just jokes & bright funny snippets of life. Pain turned into laughs. It’s also—in some memorable moments—an assessment of her pain, & the sources of that pain, itself. . . The fact is that the Catholic Church—its decrees & expectations & how those were upheld (at least at some time in her life) by family members, friends, & a heavily religious college—plays a huge role in the book & her life story. Spoiler alert: the Catholic Church doesn’t have a lot of positive things to tell Cameron about homosexuality & womanhood in general. . . And though Cameron finds welcome in the comedic world, it’s also a place where she’s been, as she writes, objectified—& where she’s been moved to help by “mak[ing] space” for other comics who identify as female. . . Save Yourself takes on challenging topics like the Church, disordered eating, and rape, but for all its serious consideration and occasional skewering, it’s hopeful and also kinda joyous, too (or maybe that’s how I felt reading it, the joy of resilience and of finding the funny). It’s that combination that’s so winning. . . 5⭐️. Save Yourself is available now. Thanks to Grand Central Pub & Forever Pub for my complimentary copy and for hosting this giveaway. All opinions provided are my own.

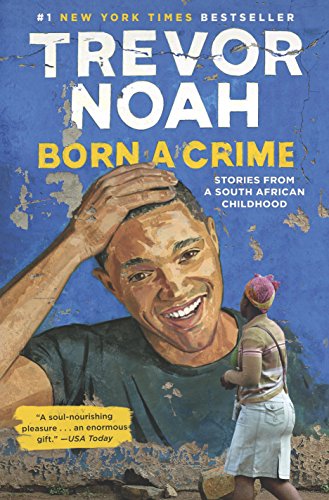

The Need to Know: A memoir that is by turns hilarious and biting, Born a Crime is highly recommended. I’m sorry to say that before reading Trevor Noah’s memoir Born a Crime, I knew very little about Trevor Noah or the tragic system of oppression known as South African apartheid. Most Americans were raised on knowledge of American slavery, Jim Crow, and segregation, even if some Americans have attempted to re-write that history to make it more palatable. But while I could gesture toward some kind of vague similarity between United States’ Jim Crow laws and apartheid or make some reference to Nelson Mandela before reading this memoir, I could say very little else. This book did not teach me everything there is to know about South African apartheid, and it does not purport to do so. But what Born a Crime does do is provide valuable contextual details about how the system of apartheid operated, some of the motivations and tensions undergirding the system, and what it was like for black and colored men and women after it ended. Importantly, Noah’s Born a Crime grounds the story of South African apartheid within Noah’s childhood, adolescence, and adulthood, and his relationships with his family, particularly his black mother, Patricia, and his white father, Robert. The book opens with an excerpt from the shocking Immorality Act of 1927—which stipulated that “carnal intercourse” between “a European” and a “native” was illicit and would result in imprisonment. I know that this excerpt should likely not be that shocking, given that United States’ Loving v. Virginia case wasn't ruled on until 1967. It’s one thing to know that these laws existed as late as the 1960s and 1980s; however, it’s another to read the words, and to hear people like Natasha Trethewey (Former United States Poet Laureate) and Trevor Noah talk about the very real impact that these racist laws had on their own births and lives. As a result of this legislation, Noah, the son of a black woman and a white, Swedish father, was, in the words of the title, “born a crime.” Told in a series of vignettes, Born a Crime offers trenchant observations on apartheid, perceptions of masculinity and femininity in South Africa, and divisions--perceived and real--between various races, languages, etc. It’s a compelling, smart cultural analysis of a system that might feel historically and currently familiar to Americans in some ways. Take this passage for example: “The genius of apartheid was convincing people who were the overwhelming majority to turn on each other. Apart hate, is what it was. You separate people into groups and make them hate one another so you can run them all.” A pervasive theme that runs throughout the memoir is Noah's uncertainty about where he belongs in his school, his neighborhood, and his family. He’s “colored,” which means, as he says, that he must determine where he belongs and who will accept him. His loneliness is profound at times. As he states in one passage, “I was like a Peeping Tom, but for friendship.” But despite the often weighty subject matter, Born a Crime also made me laugh out loud on several occasions. Like here, when Noah considers the place of Christianity in South Africa: "But the more we went to church and the longer I sat in the pews the more I learned about how Christianity works: If you’re Native American and you pray to the wolves, you’re a savage. If you’re African and you pray to your ancestors, you’re a primitive. But when white people pray to a guy who turns water into wine, well, that’s just common sense.” This book is about the sweetness and the sour. In the end, it's about the crippling social, political, and economic consequences of apartheid, and how difficult it was for Noah to fit into the strict racial and social classifications of apartheid and post-apartheid; but it’s also an inspirational story about strong womanhood and making strong men, and how Trevor is able to avoid the so-called South African “black tax” without abandoning those he loves. A wise, heart-stirring, and hilarious memoir, Born a Crime should be added to your to-read list asap. “We saw the lightning and that was the guns; and then we heard the thunder and that was the big guns; and then we heard the rain falling and that was the blood falling; and when we came to get in the crops, it was dead men that we reaped.”

Do you know that feeling that you get when you finish an amazing book but you realize that it still has a strong grip on your heart? I had it after finishing Jesmyn Ward’s brilliant, bold, and searing memoir, Men We Reaped (2013).

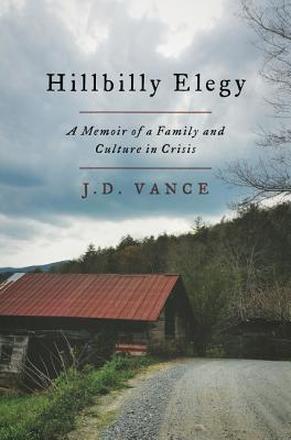

I read Ward’s Salvage the Bones (2011) a couple of years ago and thought that it was really special, so I eagerly looked forward to Men We Reaped. After reading the last stunning page, I’m convinced more than ever that Ward is someone to read—to talk about, to teach, etc.—because she offers valuable insights into what it's like being a Black American, and specific to her subject, a Black American in the South. In addition, Ward has something truly valuable to tell us about being human: how we love, grieve, misunderstand, comfort, judge, care, hurt.... You have to read this book. Men We Reaped tells Ward’s story of growing up in Mississippi interspersed with chapters which focus on the lives of five men whom Ward loved and lost between 2000-2004. The last man Ward focuses on is the first to die chronologically, and also Ward’s greatest loss, her brother, Joshua. An elegiac book, Men We Reaped pays tribute to these men—to the physical and emotional qualities which made them them—and to the community they’ve left behind. But what I also appreciated about this book is that this isn’t just an important read on how black men are oppressed, denied, and limited, but how black women face their own challenges in raising their children and trying to keep their families together and safe. Ward’s childhood is, like most childhood’s, affected very much by the relationship between her parents. Ward’s mother kicked her father out of the house for the last time after she realized that he was cheating on her again with his much younger lover. At that time Ward and her brother, Joshua, were “Both of us on the cusp of adulthood, and this is how my brother and I understood what it meant to be a woman: working, dour, full of worry: What it meant to be a man: resentful, angry, wanting life to be everything but what it was.” A wealthy white employer of her mother’s pays for Ward’s private school tuition. This, coupled with Ward’s hard work, leads to Ward going to Stanford and the University of Michigan. Her brother Joshua “had lesser models and lesser choices, and like many young men his age, he felt that school was not feasible for him.” He ends up selling crack for a while, which Ward says is not uncommon for men in their community. Later, he’s killed by a white drunk driver, who only gets sentenced to five years for killing her brother. This is a book about love and overwhelming grief, but it’s also a book about the black southern woman’s experience, the black southern male’s experience, and how those experiences are affected by also growing up poor. Though Ward ends up attending school on the West Coast and then in Michigan, she has an abiding love for Mississippi which leads her to return home repeatedly throughout her adulthood. The place, and the past, have holds on her. Ward is clear that while she has left Mississippi at times, she has not been unaffected by growing up a black woman in the South, by the “great darkness bearing down on our lives” which “no one acknowledges.” I was spellbound by the beauty of Ward’s writing and devastated by the sadness and horror of her losses. If you haven’t read her work before, pick up this book, or Salvage the Bones, both of which are gorgeous and wrenching reads. Her next book, an anthology called The Fire This Time, is already on my to-read list.  This weekend I settled in to read J. D. Vance’s Hillbilly Elegy, a buzzed-about book which has been touted as a particularly necessary read during these post-Trump election times. Hillbilly Elegy is immensely readable and immensely worthwhile. The book was revelatory to me on its own merits (i.e. as a memoir), but also because it gave me more insight into my own extended family and the general patterns of thinking and behavior amongst some white Americans which are difficult for me to understand. Vance grew up in Middletown, Ohio but also spent a great deal of time with his extended family in Jackson, Kentucky. His descriptions of where he started and how he got to where he is--a Yale Law graduate and writer with a successful marriage and career--form the meat of this memoir. Vance’s childhood and adolescence were tumultuous, to say the least. His mother is an addict who sometimes behaved erratically, and who repeatedly relocated her family as she started and ended relationships with her romantic partners. His biological father, who observes a strict adherence to his religious faith, gave up his parental rights to Vance but established a relationship with him later in his youth. In short, Vance (and his sister, Lindsay) had their share of problems to confront. Yet Vance left Middletown, Ohio for the Marines, and then went on to Ohio State University where he graduated early, and then attended Yale Law School. Vance credits his Mamaw and Papaw (his grandparents, for those of you unfamiliar with those titles) for providing him with stability, as well as his sister Lindsay, his Aunt Wee, and other role models, but he doesn’t discount the importance of personal agency, either. What Vance says is that where we grow up (the families and communities we grow up in) has a tremendous influence on our attitudes and our expectations. He cites studies which indicate that “There is no group of Americans more pessimistic than working-class whites,” a group which he counts his family (and some degree, himself) among. This information is particularly compelling when we, like Vance, consider it alongside how this same group of people has largely been so dismissive of President Obama and eager to embrace fake news (by the way: I'm not saying that these attitudes are only confined to working-class whites). Vance details his own troubled childhood and the lives of those around him to show how critical “the home” is for “hillbillies” like Vance and his family. Vance is quick to state that he is unaware of “what the answer is, precisely, but I know it starts when we stop blaming Obama or Bush or faceless companies and ask ourselves what we can do to make things better.” I mentioned earlier that this book gave me many potential insights into some of my own extended family's dynamics. My father’s family has been one that has struggled with addiction for I don’t know how many years. For the last hundred+ years, they seem to have lived in Kentucky, largely in rural Shelby and Henry counties. I didn't hear the word "hillbilly" a lot growing up, but I did hear "redneck" quite a lot, and I made a deliberate decision to try to speak without an accent when I was a pre-teen. Though my own childhood was relatively drama-free, I witnessed a couple of upsetting episodes amongst my extended family, and I heard about even more through the usual channels of family gossip. When I attempted to research that family history a couple of years ago, I discovered that not only had my grandpa struggled with addiction, but his parents had lost several children due to drowning and drinking bad milk, amongst other reasons, and his dad left the family; my grandpa’s grandpa committed suicide, leaving behind a wife and children; and my grandpa’s great-grandpa was hanged for killing his father-in-law. In other words, it seems like a long line of deep-seated issues—generations of disturbed men, and I don’t say that flippantly—many issues which I can guess at but don’t feel comfortable speculating. I would argue that my dad broke the cycle. He had flaws—like every other person in the world—but he was an excellent father and an excellent role model. Anyone who knew about the family that he grew up in wondered how he managed to make it out and thrive like he did. I’ve long wondered about the role that “the home”—one’s environment, and also, one’s genetics—play in family development, particularly in isolated rural communities, and how we reconcile that with we can do and choose to do by making our own decisions. I loved this book because Vance’s life was interesting and even inspirational, and I enjoyed reading about someone else who calls their grandparents Mamaw and Papaw like I do, and who loves his family even while suffering under the demands placed upon him by some of those family members. But what I loved most is how Vance writes about the role that our past plays on us in rural communities like where I grew up—how it shapes our actions and who we are and who we become—but how he also emphasizes our own agency in the process. I’ll take Vance’s thoughts with me as I continue to consider how my family ended up the way that it did—with my dad blazing his own path—and when I think about my hopes for son’s future. And finally, when I think about where things stand in our country politically. I don't think that "hillbilly" problems will be solved quickly, but it seems like Vance's book provides more illumination and allows us to see them better. |

About me.Give me that HEA, please.

Join my mailing list.Want to receive a weekly email with links to my latest blog posts? Sign up below!

Archives

April 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed